What Are Bonds?

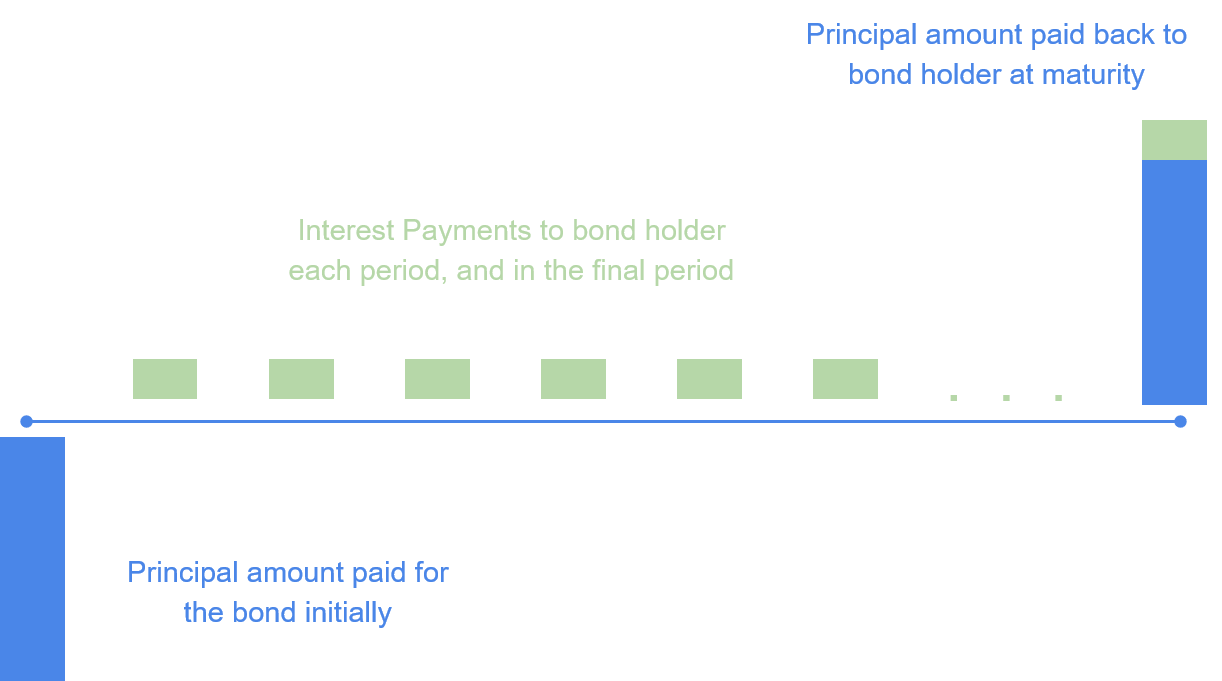

Bonds essentially functions as loans where the holder of the contract can exchange hands. It is a type of fixed income security where the borrower initially issues a bond and sells it for a principal amount to a lender. The borrower promises to pay interest to the lender periodically in the form of coupons, and return the principal amount at the expiry date of the contract. The bond contract specifies terms like expiry (maturity) date, coupon yield, and other conditions.

Capital Structure

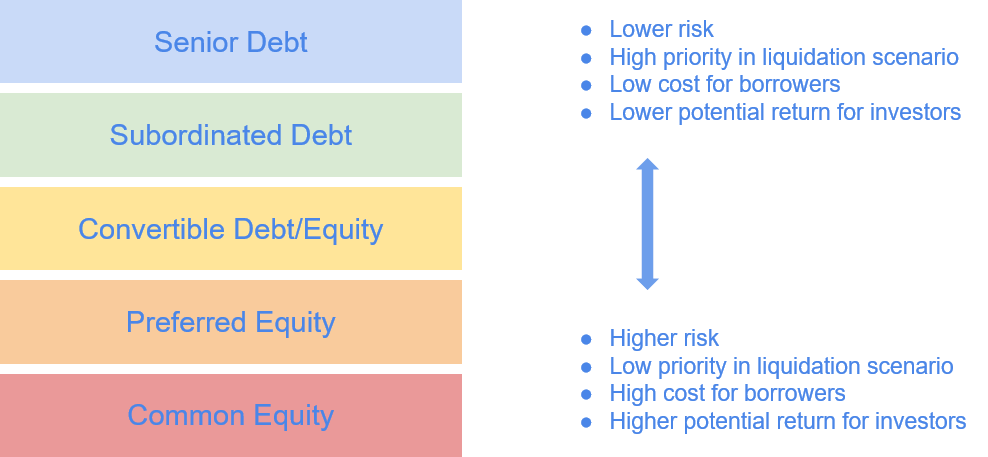

When companies need to financing, they can either issue debt or issue equity. If they choose to finance through issuing bonds, a type of debt, then they are promising to pay back the principal amount borrowed and some interest. Because issuing debt is a promise to pay someone back, debt holders are paid backed before equity holders in the event of bankruptcy or liquidation. Although debt and equity are the main categories of financing, there are many sub-categories in the capital structure. We will display these subdivisions in the diagram below, but will not discuss them extensively. The main concept to understand is that there is a risk-reward dynamic in the capital structure like in all of finance. Debt holders are the first to get paid back, but because of that priority of lower risk, their returns are limited to interest payments. Equity holders are the last to get paid back, but because of that assumption of higher risk, their potential returns are only limited by how profitable the company is.

Math and Terminology

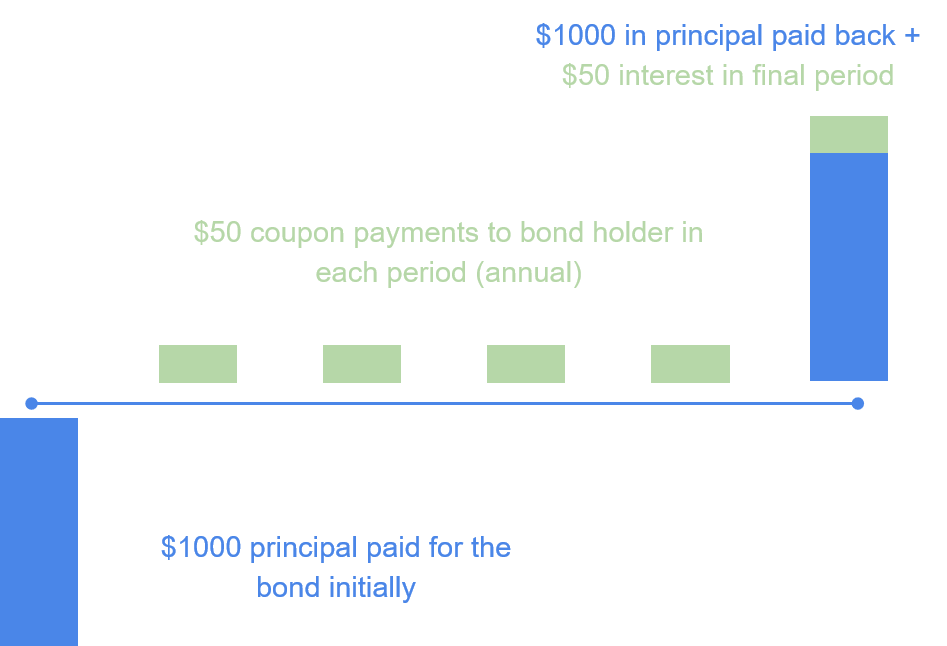

To have a solid understanding of bonds, there is no avoiding at least a moderate amount of math and a few important terms. Let’s imagine that a company needs to finance a project and decides to issue some bonds. It issues 1 million dollars worth of bonds at a par value of $1000 with an coupon of 5% paid annually and a maturity of 5 years. What does this all mean?

- Notional Amount - total amount raised, in this case $1 million.

- Par Value & Face Value - the stated value on the bond contract. Par value and face value are synonymous. In this case, a $1 million notional offering means 1000 bonds at a $1000 par value. It is also the amount of principal paid and returned per bond contract. It is usually either in $100 or $1000 sizes.

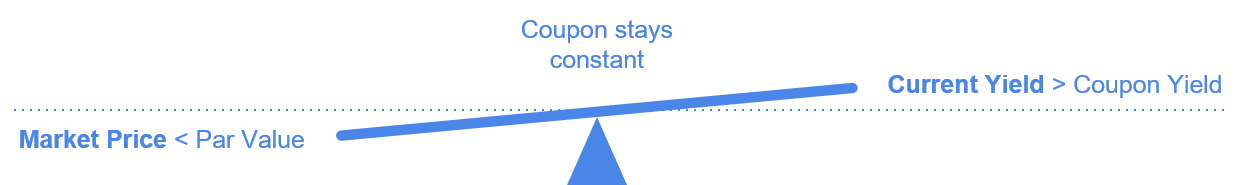

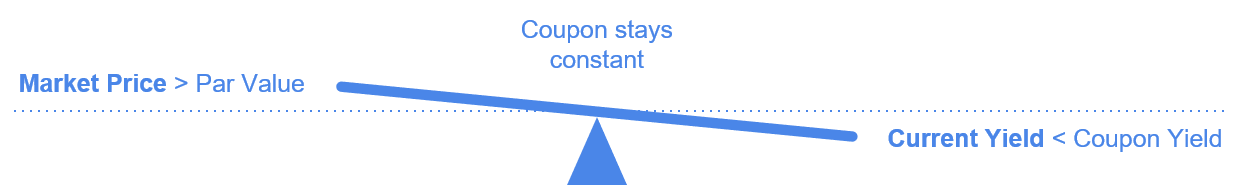

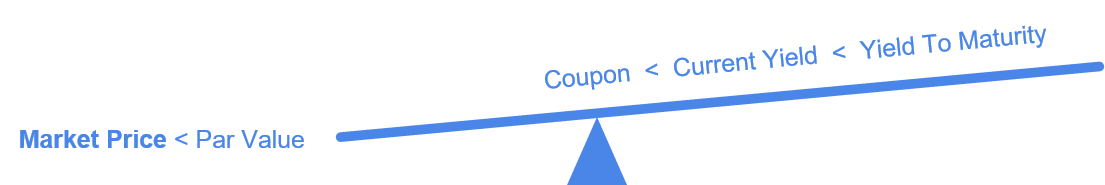

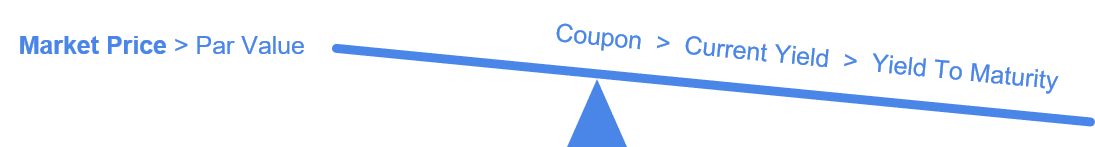

- Market Price - the price that the bond trades at. This may be different from the par value of the bond because of various factors such as interest rates and the company’s financial stability. This price is usually quoted as a percentage of par value and not necessarily the dollar amount. For example, a $100 par value bond trading at 101 means 101% of $100, which is $101. However, a $1000 par value bond trading at 101 means 101% of $1000, which is $1010. Bonds that trade above par are trading at a premium. Bonds that trade below par are trading at a discount

- Coupon - the amount of interest paid per period. This can be expressed as a dollar amount or as a percentage of the par value. For example, a $1000 par value bond with a 5% coupon pays out $50 per period, no matter where the market price is trading at.

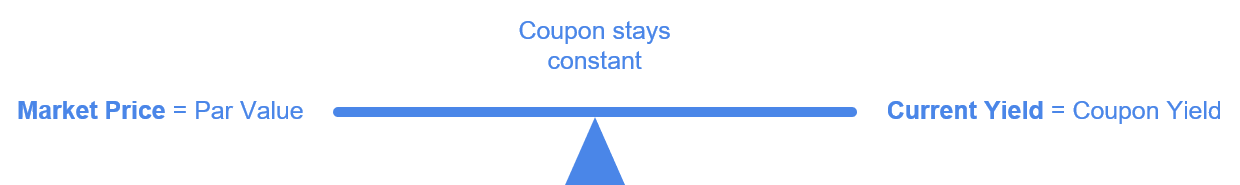

- Yield - the return that the investor gets for a given market price and coupon rate. There are actually various types of yields which we will discuss on the next page, but for now, we will use the current yield, which is defined as coupon / market price. For example, a coupon of 5% on a $1000 par bond trading at $900 has a current yield of $50 / $900 = 5.56%.

- Maturity Date - the date on which the bond contract expires and principal is paid back. In this case, the maturity is 5 years, which means it will expire 5 years from the date that the bond was issued.

Types of Yields

Current Yield

As described, current yield measures the yield on interest payments for a given coupon amount and market price. This yield changes with the market price from the perspective of investors considering buying the bond. But after we purchase a bond, we secure that yield for the remainder of the bond’s life. This does not take into account the gain or loss associated with the difference in the bond’s market price at the time of purchase and its par value. The formula for current yield is:

- Current Yield = Coupon Rate / Market Price

For example, consider our previous example where a $1000 par value bond with a 5% coupon is trading at $900. Its current yield is $50 / $900 = 5.56% if we decide to purchase it at this moment. Let’s imagine in a few months that the bond’s price rises to $1100. The current yield then becomes $50 / $1100 = 4.55% for new investors who wish to purchase the bond, but because we already hold it with an initial investment of $900, our yield is still 5.56%.

Yield to Maturity

Like current yield, yield to maturity, or YTM, calculates yield based on the coupon rate and the market price. However, in addition to this, YTM also considers the difference in market price from par value when calculating yield. This YTM assumes that we not only receive the coupon payments, but also holds the bond to maturity and gets the par value principal repaid to us. Using the previous example, we will highlight two scenarios:

- Discount to Par - When the market price is trading at a discount to par, the current yield is higher than the coupon rate because we are getting the same coupon despite paying a lower price. Paying a discount to par also means that we will realize a gain when we are paid the par amount at maturity. This gain is an addition to the yield we get if we hold to maturity, which means YTM > current yield > coupon.

- Premium to Par - When the market price is trading at a premium to par, the current yield is lower than the coupon rate because we are getting the same coupon despite paying a higher price. Paying a premium to par also means that we will realize a loss when we are paid the par amount at maturity. This loss lowers the yield we would get if we hold to maturity, which means YTM < current yield < coupon.

Market Price Fluctuations

Bond prices may fluctuate in the market away from par for various reasons. We might find bonds trading at discounts to par because the market believes that there is a risk that the company might default on its debt. The higher the risk, the steeper the discount because no one wants to own something that might not be paid back. Note that steeper discounts translate to higher yields, which is reminiscent of the risk-reward dynamic. Another reason why bonds might trade at discounts is that there are other high yielding bonds in the market. When interest rates rise in general, what was once an attractive bond yield becomes less attractive by comparison to other higher interest rates, so price has to lower in order for the bond to trade at an attractive yield again.

On the other hand, bonds might trade premiums because interest rates have gone down. What was once a fair interest yield might suddenly become more attractive because other interest rate yields are lower by comparison. This bond’s attractive yield would experience high demand, causing the price of the bond to be bid-upwards. Bonds that are deemed as safe havens might also see increases in price during periods of fear in the market, which leads to strong demand for safe assets.

One important pattern that is useful to always remember is that prices move inversely to yields.

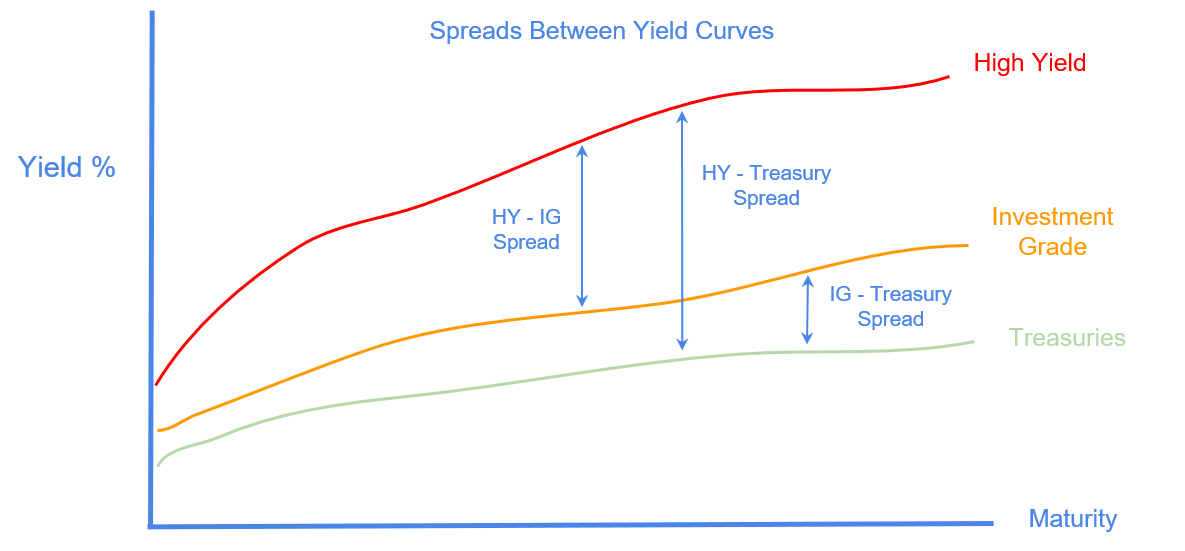

Spreads and Risk-Return

Within fixed income, there are many types of securities. They have varying degrees of yields based on their perceived risk levels. While municipal bonds, mortgages, and ABS all fall within fixed income, for purposes of illustrating the concept of spreads, we will mainly use the examples of treasury bonds, investment grade corporate bonds, and high yield bonds.

Treasuries

Federal government issued securities are usually considered the safest fixed income investments. These securities, like the 10-year treasury, are often used as benchmarks for measuring yields. Sometimes, other fixed income instruments are quoted as spreads above a benchmark treasury rate. A spread in this instance refers to the difference in yield between two assets. It symbolizes the additional yield that investors must be compensated to take on additional risk above the risk free rate of the treasury. Note that comparisons should be made between bonds of similar maturity. Looking at a 30-year treasury bond and a 5-year corporate bond would not yield as meaningful information as a 10-year treasury with a 10-year corporate bond.

Investment Grade Bonds

These bonds are issued by high quality, established companies. The term investment grade refers to the quality of the bond and the health of the company issuing the bond. Profitable, minimally leveraged companies issuing bonds will more likely have an investment grade rating than struggling or very leveraged companies. Note that being investment grade allows companies to easily access the debt market for financing because they are able to raise money at a lower interest rate cost since they are less risky.

High Yield Bonds

These bonds are issued by lower quality, struggling companies. The term high yield refers to the quality of the bond and the health of the company issuing the bond. Struggling or highly leveraged companies issuing bonds are more likely to be classified as high-yield because of the higher yields they must pay investors to compensate for elevated risk. When a company is having trouble staying profitable or has too much debt to service, it has a higher chance of defaulting on debt. Companies try to avoid being classified as high yield because raising debt in this market is very expensive - issuers have to compensate investors with attractive interest rates.

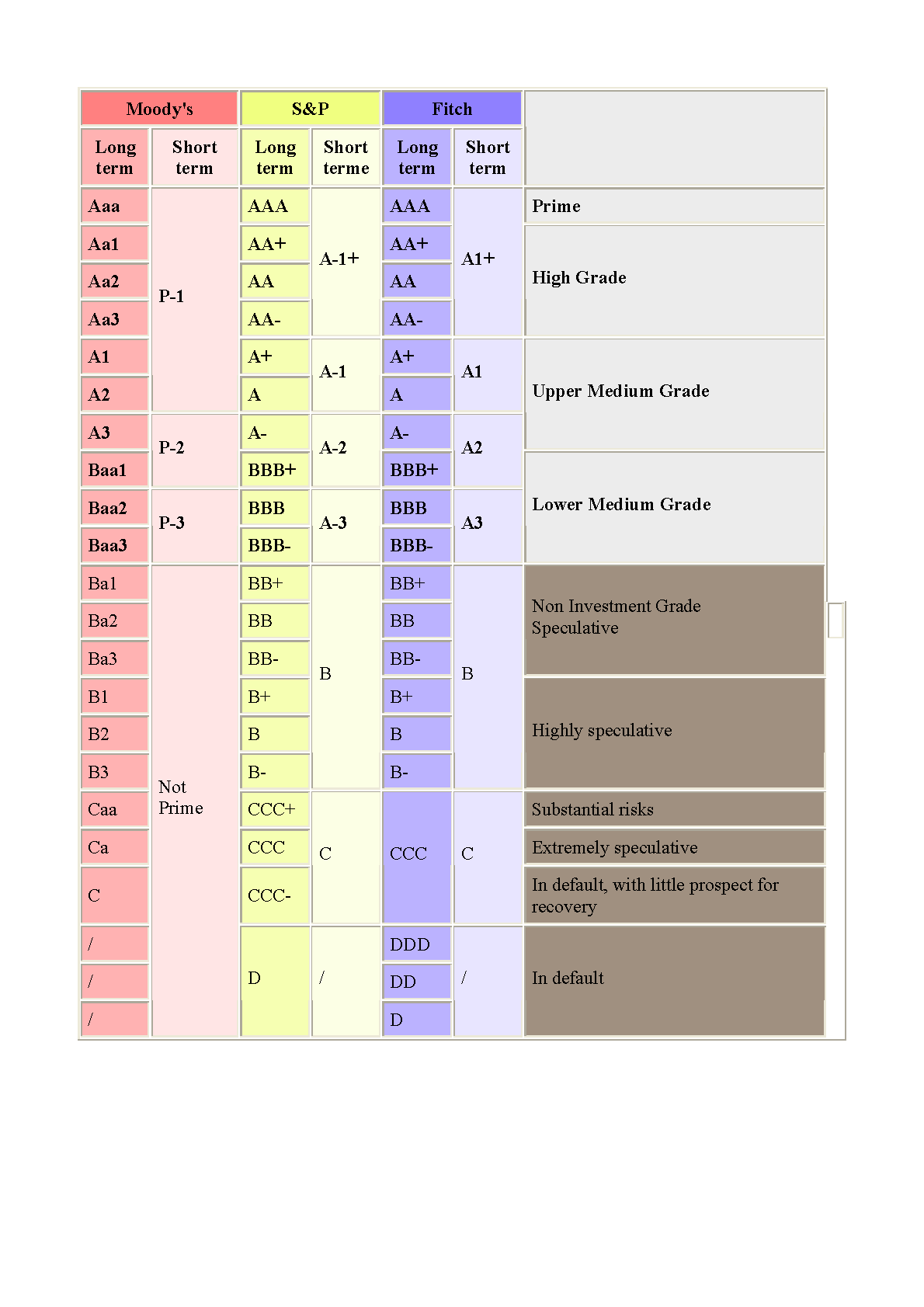

Credit Rating Agencies

Who determines if a company falls in the investment grade or high yield category? Credit rating agencies like Moody’s, S&P, and Fitch assign ratings to the debt of different issuing entities like governments and corporations. They each have their own rating system, but there is a generally agreed upon threshold for what constitutes as investment grade or high yield. However, buy-side investors must do their own research of course. These rating agencies only provide guides, but portfolio managers need to do their own research before deciding to invest. After all, if everyone just followed the rating agencies’ guidelines with no independent thinking, then markets would be pricing assets very inefficiently.

Inflation

Bonds are a great asset for predictable income. However, under certain economic conditions and expectations, bond portfolios can take a hit. Understanding the macro drivers of fixed income markets is a crucial complement to understanding the company specific risks of each bond. The following drivers are the main macro contributors to bond market fluctuations:

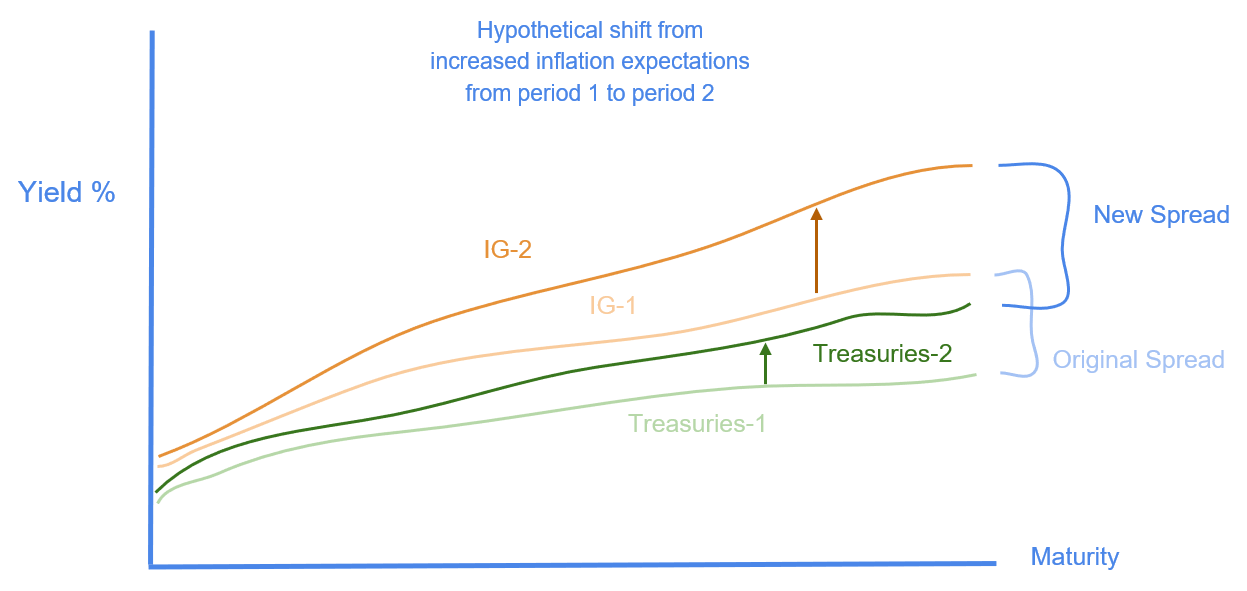

Inflation

A general rise in prices of goods and services across the board is referred to as inflation. When prices rise, each dollar is worth less because we are able to purchase less for a given dollar amount. When we think of bonds, the interest payments we are entitled to receive will be worth less in the future if inflation causes the purchasing power on our interest to decrease. Therefore, a rise or expected rise in inflation is not good for bond prices. Let’s imagine that there is an expect rise in inflation. To compensate for the decreased purchasing power of future interest payments, bonds need to adjust to offer higher yields to investors. How do yields rise for bonds? Yields move inversely to prices, so for a bond to offer a higher yield, the market price of the bond has to decrease.

Interest Rates

Although inflation is a primary theoretical driver of bond market fluctuations, benchmark interest rates are what pushes price movements in practice. When markets expect a rise in inflation, benchmark interest rates like interest yields on treasuries rise concurrently with a drop in the treasury bond market prices. The rise in yield of these risk free assets pushes up the yield in riskier assets. How does this work? Imagine we own a 3% yielding corporate bond when treasuries are yielding 2%. If treasury yields all of a sudden rise to 3%, why would we hold a riskier asset that doesn’t give us any additional return? We would sell the corporate bond and buy the treasury, driving prices of the corporate bonds down and their yields up, thus as shift upward to maintain the spread and risk-premium of corporate bond yields.

Review

Even if we are equity investors who are less concerned about the fixed income asset class, a fundamental understanding of its role in the economy is helpful in making better investment decision. Knowing how bond market movements signal macroeconomic perspectives is just as important as paying attention to company-specific fundamentals. Next, we will discuss how various asset classes interact with each other.