Underlying Assets

At the base level, there are different asset types like stocks, bonds, loans, mortgages, etc. When there are securities created to track, mimic, or vary in other ways depending on the price of the original asset, we call the original asset the underlying asset.

Stocks are the standard, vanilla shares of companies that represent ownership of equity. Bonds are the standard, vanilla securities that represent a contract of ownership of debt. Below is a beautiful vanilla plant.

Other “base level” assets include commodities, currencies, etc. Note that assets like mortgages and car loans are at the base level, but the asset backed securities are not - they are packaged instruments of pools of underlying assets.

ETFs

The exchange traded fund has opened up a new world of possibilities for the retail investor. When an individual does not have the money or time available to create a custom diversified portfolio, but still wants the liquidity of exchange traded securities, the ETF is a combination of features, the best of both worlds. In comparison to index funds, it may have higher trading costs like brokerage fees, but many investors are willing to incur that cost for the high liquidity it provides. Of course, note that with so many ETFs out there, only the most popular will have the liquid trading that gives it a distinct advantage over other options. The mechanics of the fund are similar to mutual funds, but the distinction is that the fund’s shares are traded on an exchange, which can be bought and sold like stocks by investors.

ETFs, which offer a variety of options for diversified exposure to themes like healthcare, technology, sustainable investing, benchmark indices, etc, have become a staple of passive investing. The notion of passive investing is that over time, letting capital markets do the work for us is more efficient than incurring high costs of fees in actively managed mutual funds or hedge funds that might not outperform the market. The debate is ever present, and because each side provides unique advantages, both strategies play important roles in investing for different types of investors.

Derivatives

Derivatives are financial instruments that get their value from and change with the price of an underlying asset. There are a diverse set of derivatives that allow us flexibility in the types of exposures we want, but two fundamental types are futures and options.

Futures

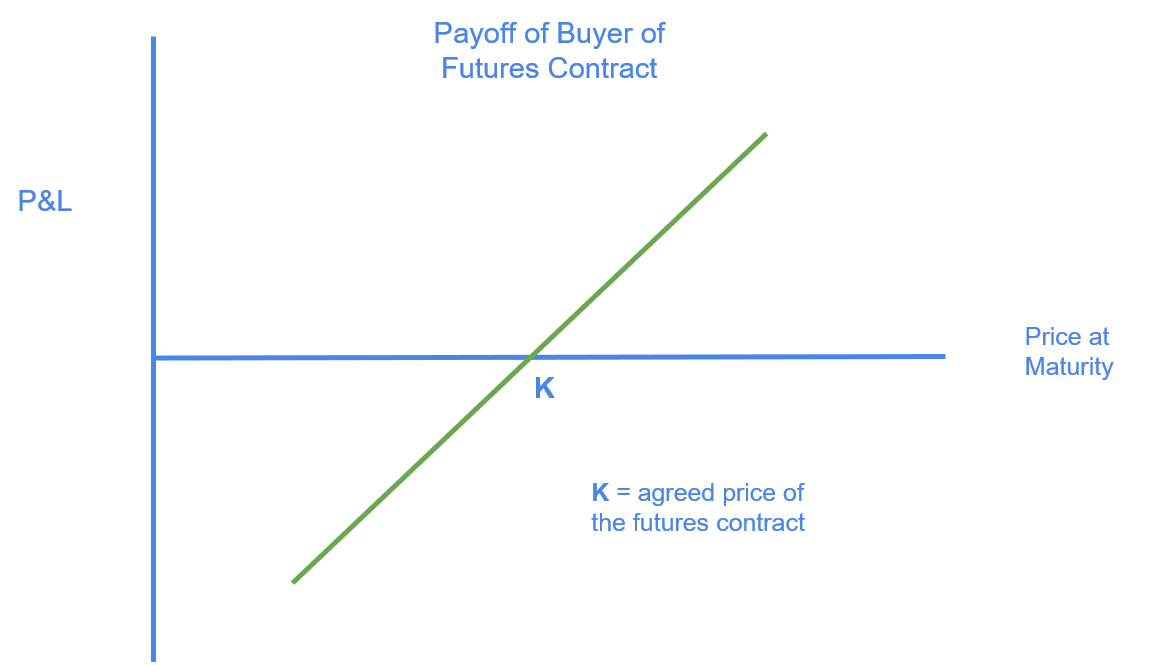

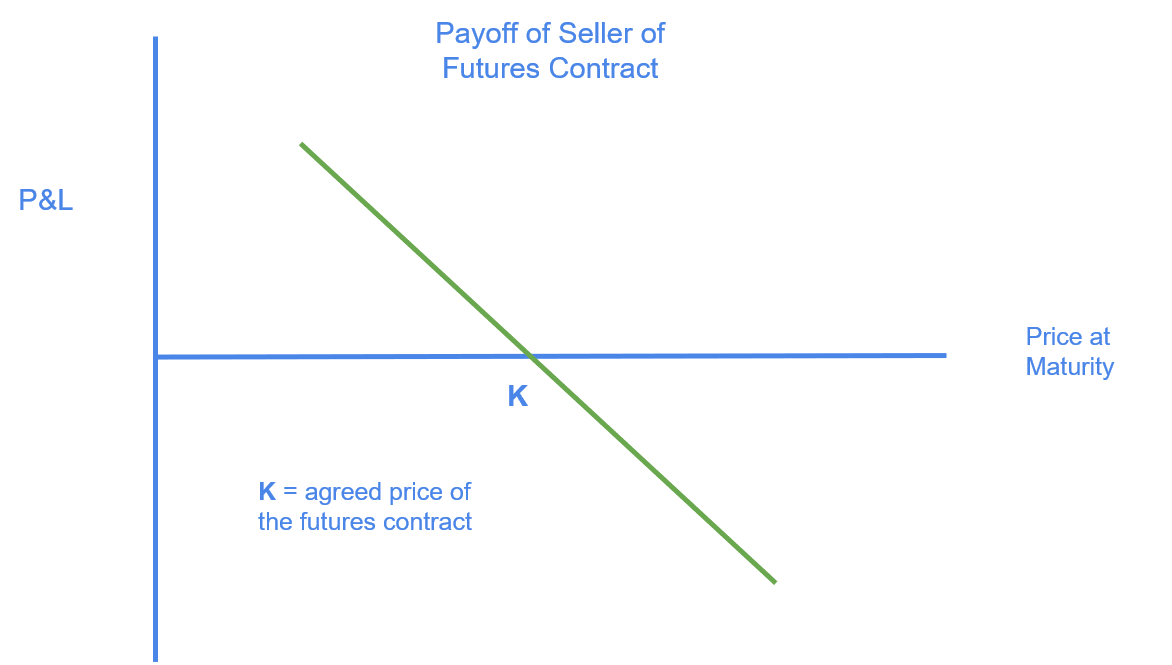

Futures are contracts between a buyer and seller to execute a transaction at a certain price at a certain date in the future. For example, there are futures on the price of oil. For example, a futures contract on WTI crude oil may be an agreement between a buyer and seller to exchange a barrel of crude for $60 three months from now. Unlike options which give the holder the choice to execute the transaction or not, futures are agreements that both sides honor. Futures have different functions for different sides of the market. An oil producer may want to enter a contract on the side of a seller to lock in a price to sell its oil in the future. A manufacturer that uses different types of oil as a raw material may want to enter a contract on the side of a buyer to lock in a price buy buy its oil in the future. Although futures can be used for trading and speculation, we will discuss them from the perspective of hedging.

Imagine we are an oil producer and the current price of crude is at $60. We have a neutral outlook on the price of oil in the next year, giving it an equal chance of going down or up. We think $60 is a good enough price for us and are willing to give up potential upside (a scenario where the market price of oil goes to something like $70 a year from now) to protect ourselves from the downside (a scenario where the market price of oil goes to something like $50 a year from now). Once entered into the contract, we are guaranteed the $60 price once we actually deliver our oil inventory a year from now.

Options

Options are also contracts between a buyer and seller to execute a transaction. However, the holder of the option - the person that buys it - has the choice, but not obligation, to exercise that option at any time up to and including the expiration date. Note that American options holders have optionality for the period up to expiry while European option holders have optionality only on the expiry date. We will only discuss American options in this lesson.

As mentioned, because the option give the holder a choice but not an obligation, there is value to the contract instead of a two-sided binding agreement in futures. Because of this additional feature, there is a premium a buyer has to pay when buying an option that does not exist for futures contracts. This premium is the cost of optionality, a term that can be summarized conceptually as a guarantee of a certain outcome with the potential for more.

There are two types of options:

- Call - the right, but not obligation, to buy a security at a certain price up to a certain date in the future.

- Put - the right, but not obligation, to sell a security at a certain price up to a certain date in the future.

Call - Imagine that we are looking to buy a piece of land in the Caribbean to build a beach house. We find a plot and really like it, but do not have the money yet, or would like to wait for a bit before buying it. We can theoretically enter into a contract with the seller to buy it from him at a certain price by a certain date, a call option. Let’s say we agree with him on a price of $100,000 and a period of 6 months. Because we would have optionality as a holder of the contract, he will charge us a premium of $10,000 for the right to buy the land. Then, a little less than 6 months later, one of three scenarios might happen.

- The initially assessed value of land was correct, and we end up paying $110,000 for a $100,000 piece of land and the time/optionality premium, and alright deal but not the best.

- The value of the land is re-assessed to $20,000 - someone discovered that the foundation of the land is on top of an empty cavern, and it might collapse any day. We still hold the contract for the right to buy it for $100,000, but obviously we would not buy it now. Therefore our loss is $10,000 (the initial premium) instead of $80,000 had we paid the $100,000 upfront price six months ago. We avoided some serious trouble!

- The value of the land is re-assessed to $200,000 - someone discovered that there are scattered gold coins buried beneath the land from a pirate ship wreck 200 years ago. We still hold the contract for the right to buy the land for $100,000, so we end up paying only $110,000 for a $200,000 piece of land. A great deal!

The same but inverse scenario can be said for put options - the right, but not obligation to sell. The seller of the land, instead of agreeing to sell a call option to the buyer, can negotiated and bought a put option from the buyer. In this scenario, the seller could have paid the buyer a $10,000 premium to secure the right to sell the house at $100,000. If it ends up being worth $20,000, the seller can receive $90,000 ($100,000 - upfront premium), avoiding an $80,000 loss. If it ends up being the same, then the seller receives $10,000 less than he would have without the contract, a price to pay for the protection. If it ends up being worth $200,000, the seller doesn’t have to exercise the contract, and can just sell the house outright at $200,000 and will end up receiving $190,000 after counting the cost premium of the put contract that was initially bought.

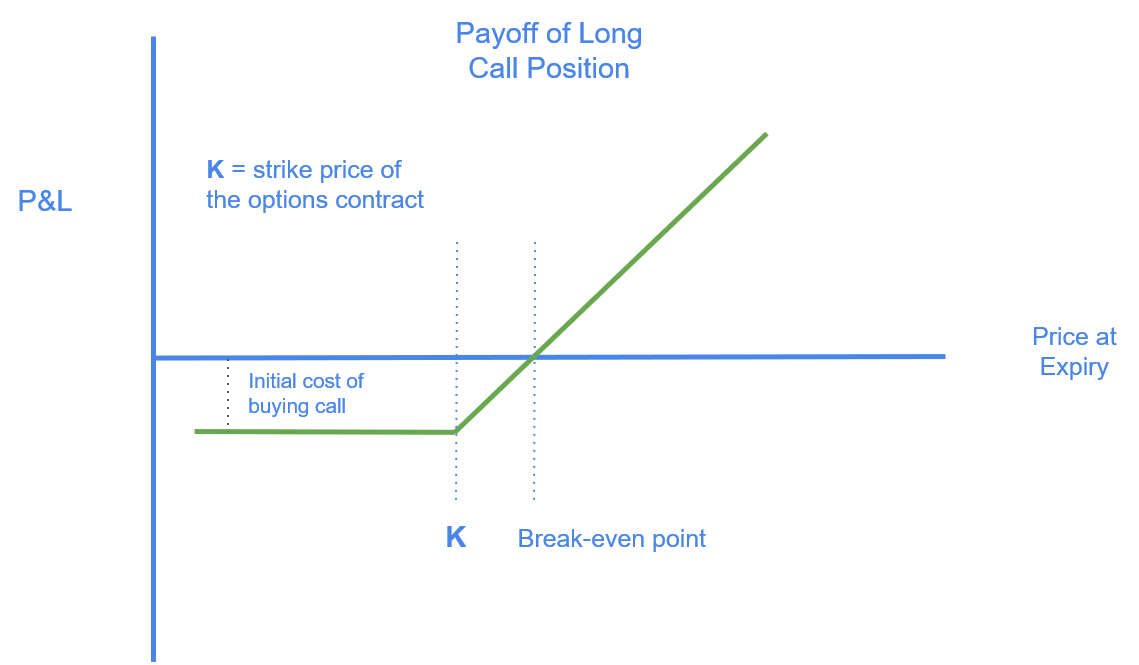

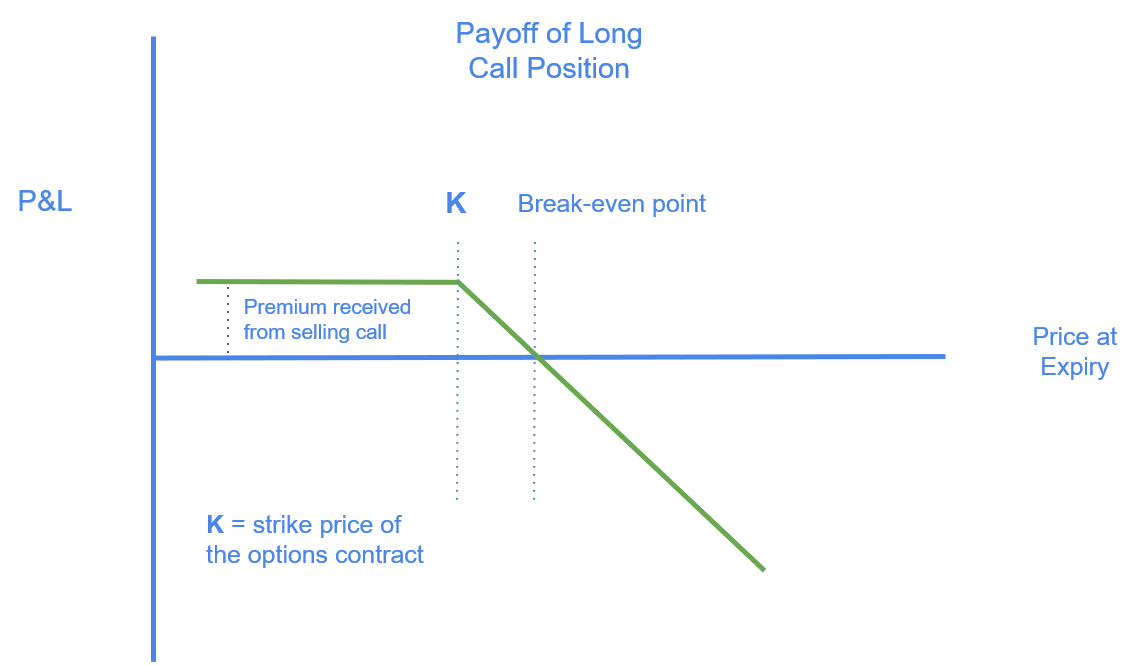

Options are applicable to physical assets, but are even more relevant for financial assets. Options exist for almost everything, including stocks, bonds, FX, interest rates, etc. The same principle applies across asset classes, but we will use stocks as an example. Below are payout diagrams of options, but before that, just a note on the terms long and short.

- Long - when we are long an option, we are the holders that bought the right to buy (call) or sell (put), for a premium, from the seller of the option.

- Short - when we are short an option, we are the sellers that sold the contract for a premium to the buyer of the option. We are obligated to honor the contract. For calls, the holders have the right to buy from us at a certain price. For puts, the holders have the right to sell to us at a certain price.

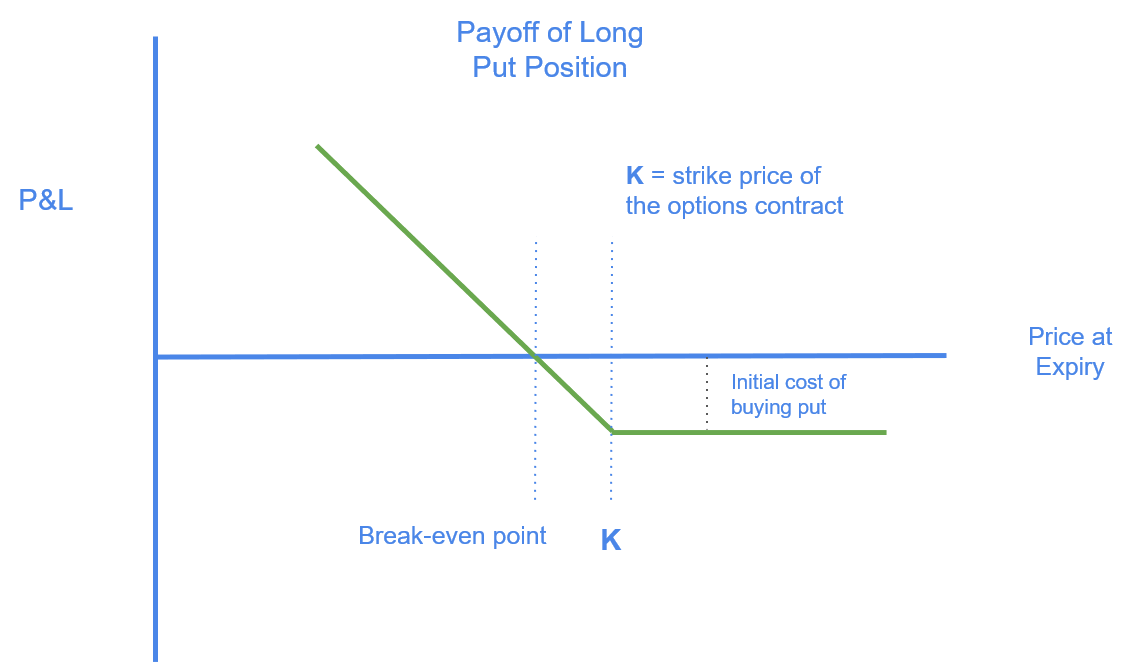

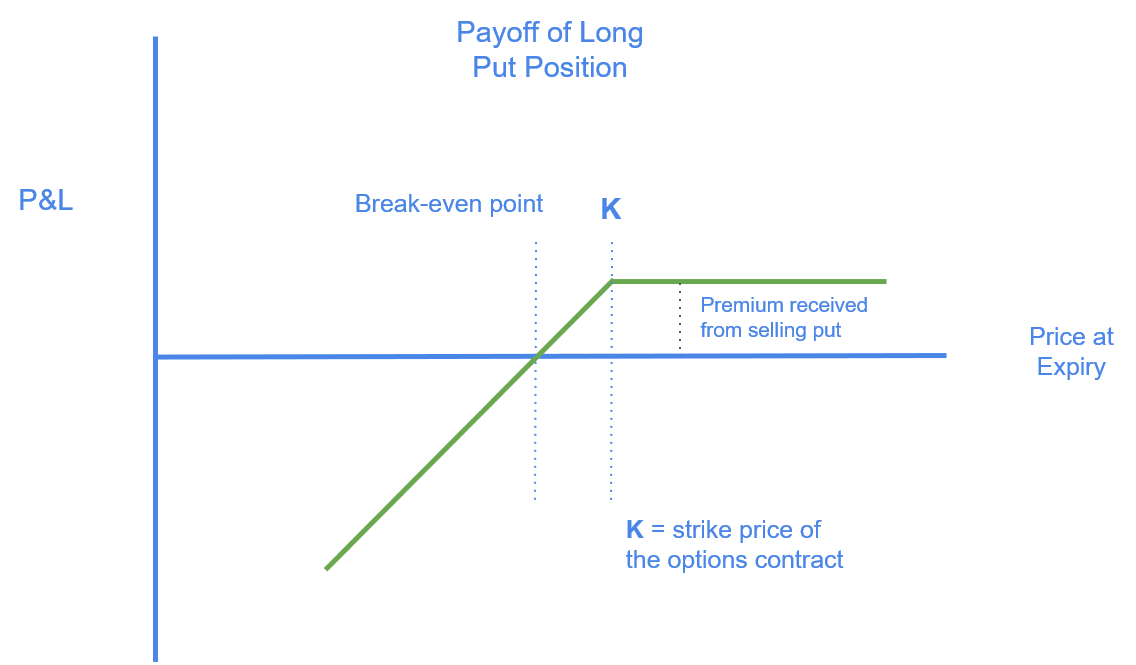

Imagine a stock currently trading at $100. We will examine a variety of options positions that have a maturity of 6 months from now and their payout diagrams at expiry. Below, the x-axis is the market price of stock at expiry and the y-axis will be the profit and loss, or P&L, we will receive at expiry. The strike price is the price agreed upon in the contract to buy or sell the stock.

Let’s pretend that the premium of the call is currently $5, and we buy it today to enter into a long position as the holder of the call. If the stock is trading at $100 at expiry 6 months from now, we will lose the premium and nothing else. If the stock trades anywhere below $100, we still only lose the premium. Because of the optionality, like in the Caribbean example, the maximum we can lose by holding the call option is the premium we paid upfront, or $5. If the stock trades above $100, we make back our initial cost until we break even at $105. This is because if we exercised the call, we have the right to buy a $105 stock for $100, our agreed upon strike price. This $5 profit from exercising the contract is canceled out by the $5 premium we paid upfront. If the stock trades above $105, each dollar is an additional dollar of profit. For example, if it rises to $120 in the market, then we can buy the stock at $100, count the $5 upfront cost, and sell it at $120 for a $15 profit.

Let’s pretend that the premium of the call is currently $5, and we sell it today to enter into a short position as the seller of the call. If the stock is trading at $100 at expiry 6 months from now, the call is worthless and we keep the $5 premium we received. If the stock trades anywhere below $100, the call is still worthless, so we keep the $5 premium we received. If the stock trades above $100, the premium that we get to keep is reduced until we break even at $105. This is because if the holder exercised the call, they have the right to buy it from us at $100, our agreed upon strike price. The $5 premium we received from selling the contract is canceled out by the fact that we have to honor the contract - buy the stock at $105 in the market and sell it to the call holder for only $100.

The same can be said for put options. Let’s pretend the premium is at $5 and we buy it to become long the put. If 6 months from now the stock doesn’t move, it expires worthless. If the stock trades below $100, we make back our initial cost until we break even at $95. If it goes below $95, we profit a dollar for every dollar it drops. If it goes above $100, the maximum we lose is the premium we paid, $5.

If we sell the put at $5, we become short the put. If 6 months from now the stock doesn’t move, the put expires worthless and we keep the $5 premium. If it trades below $100, the premium we initially received is reduced until it reaches $95, at which point we break even. If it trades even lower, we lose a dollar for ever dollar below $95. If it trades higher, then the put will expire worthless, and we get to keep the premium we initially received.

There are still more characteristics about options like time decay, implied volatility, etc, but we will not discuss them here.

Review

We have gone over asset classes, the vehicles and platforms we can invest through, and now the major types of investment products. While some of these products are suitable for all investors, derivatives are more risky and require a deeper level of understanding to master. We do not discourage you from trying new things out if you are the curious type, but just bear in mind the types of risks that you are taking on in the investment process. The variety of products can satisfy most types of investors, but although the products are interesting, the process of forming an investment thesis is the bread and butter of the profession. In the next few lessons, we will discuss how to understand a company and value its stock.